What is QKD

Quantum Key Distribution [Xu_2020] generates a random string for two players Alice and Bob. Physics guarantees that under some assumptions an evesdropper Eve cannot know anything about that string. The security of QKD can be formally proven [Tomamichel_2017]. However, any actual implementation of QKD is vulnerable to attacks that exploit imperfections such as information leakage into side channels. Proper security analysis and countermeasures against known attacks are thus also part of a QKD system.

Even though an actual system is never fully secure, it is important to understand that QKD provides hardware-based security as apposed to computational security. QKD thus perfectly complements classical crypto and post-quantum crypto.

Standardization is an important and ongoing process for QKD systems. There are the ETSI GS QKD 016 common criteria for prepare and measure QKD modules, among other documents...

QKD networks can be logically organized in layers. For example in openqkdnetwork.net there is the hosts layer for the application, the key management layer to manage QKD keys, the quantum network layer to control the routing and finally the quantum link layer with the physical devices. In a good design, all layers are fairly independent of one another. The QKD system we present here is the physcial device in the quantum link layer.

There are a number of different ways to do QKD from the physics point of view. The choices one might have are

- Prepare and measure vs entenglement-based

- normal vs (semi-) device independant

- discrete variables vs continuous variables

- single photons vs coherent states vs entangled states

- a multitude of encodings: BB84-like, high dimensional, differential phase shift, etc.

Our system is prepare and measure, discrete variable, no device independence, with coherent states.

Understanding Key Rate

From a user perspective, the performance of a QKD system is measured by its keyrate. It depends on only a few physical parameters. Understanding those simplifies network considerations by a lot.

The most important factor is the loss in the fiber. The probability of detection decreases exponentially with the fiber length. The final keyrate is proportional to the repetition rate at Alice and the probability of detection.

The second parameter is the qubit error rate: the probability to measure the wrong result at Bob. These errors need to be corrected and the information leakage during both the generation and correction of the errors compensated. This is called privacy amplification and compresses the key. There is a threshold above which no key generation is possible.

The third factor are finite size effects. The raw key is processed in blocks that need to be sufficiently large. The smaller the blocks the less efficient the postprocessing is. This effect becomes important for very low count rates and if the user does not want to wait for a long time before getting the first key.

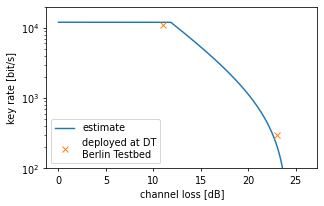

Below we show an estimation of the keyrate vs channel loss. There is a maximum detector count rate. There is an exponential decrease at medium loss and a drop off due to dark counts, which increase the qber. The curve in the plot is \[ R(1 - h(q)), \] where \( q \) is the qubit error rate, \( h(q) = -q\log(q) - (1-q)\log(1-q) \) the binary entropy function and \( R \) the click rate with matched bases. This curve does not take finite size effects into account (the data points do).

Impact of components

Laser

The system runs well with a non-tunable CW laser with 100kHz bandwidth and center wavelength at around 1550nm.

The allowed center wavelength depends on the components chosen: the beam splitters in the interferometer, optical filter, modulators. We tested the system between 1530nm and 1570nm. The qber went up slightly from 4% at 1550nm to 6% at 1530nm and 1565nm.

The bandwidth of the laser must be small enough to interfere with high visility on the unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometer. We can roughly estimate the qber contribution as \( 1 - \exp(-\tau/\tau_c) \), where \( \tau_c \) is the coherence time and \( \tau \) the delay of the Mach-Zehnder.

The stability of the laser must be good enough to allow phase stabilization of the Mach-Zehnder interferometer (which is done based on SPD counts, which is slow). As a rule of thumb, a pi phasedrift of the Mach-Zehnder interferometer should be of the order of 1s or slower. This is fine for thermal drifts. However, if the laser is tunable, it will often actively tune the center wavelength. We tested two tunable lasers. Only one of them worked in it's ultra-narrow linewidth mode: The RIO COLORADO Widely Tunable 1550nm Narrow Linewidth Laser Source.

Detector

The detector is a crutial component of the system because it directly influences the key rate through the maximimum click rate, maximum gate rate (repetition rate) and it's contribution to the qber from dark counts and afterpulses.

We use the Aurea OEM module in gated mode. Additionally we apply software filters around the peaks to reduce background as much as possible. We set the dead time to around 20us. Interestingly, we noticed that changing the detection efficiency setting between 10% and 20% yield similar key rates. Even though the count rates are higher at a higher detection efficiency, the qber also goes up and/or the dead time needs to be increased.